DESIGN STUDY: MAX BILL & CONCRETE ART

So so sorry for the radio silence. I was in over my head with market and moving from LA to NY. I think I let a month go by since I've done any sort of design research. Woops! And though I'm still super busy and not in the mood to do anything after hustling so hard, I have been looking at the work of Max Bill lately, so I figured it was time to get back to it.

Max Bill was born in Switzerland in 1908. In his home town of Winterhur, he apprenticed as a metalsmith before studying at the Bauhaus school in Dausau, Germany in 1924. Like most Bauhaus artists, Bill worked with a number of mediums and designed across genres.

Some of his most notable work in my opinion is in his graphic work, which included typography.(Yes!) But then again I also love the architectural pieces, sculptures and industrial designs he did too, so maybe I actually just love Max Bill.

What's really cool about Bill is that he studied under Bauhuas, but he also hung out with French painters like Hans Arp and Piet Mondrian, whose work represented a movement then called, Abstraction-Création, which influenced him to form his own group known as the Allianz Group in Switzerland in 1937.

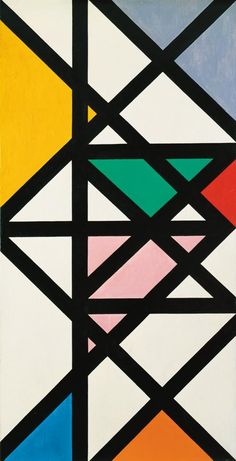

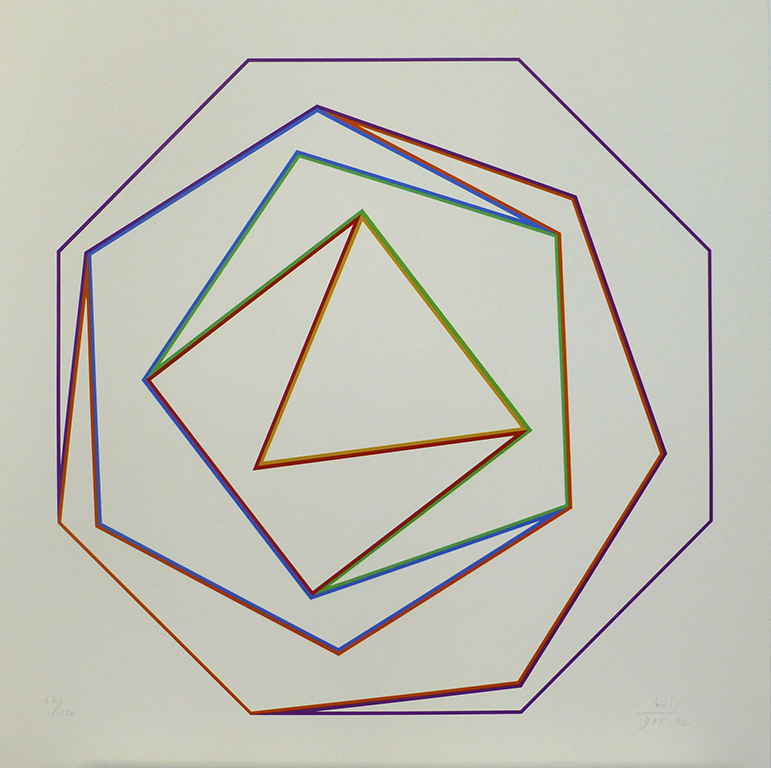

The Allianz Group focused on Concrete Art theories pioneered by Max Bill, which was similar to Constructivism, in that both were interested in abstraction, but Bill's theories made a heavier emphasis on color. (A good student of Bauahaus, I'd say)...

A major tenant of the larger Concrete Art movement of the time, which was the probably the most distinguishing departure from Constructivism, was that Concrete Art strived to make no references to objects found in visible reality or in nature. So out went all the boring notions of cubism and in came really cool shapes.

Once Constructivism spawned in Russia around 1919, its influence on artwork made in Europe lasted through the 1930s. And while Bauhaus ended up a movement in its own right, some of the Bauhaus instructors such as Josef Albers, worked to create the Concrete Art movement. (See my previous posts on Josef Albers for more info). After studying with Bauhaus, hanging out with super cool French painters, and starting his own art group, Max Bill went on to teach at The School of Arts in Zurich in 1944, before forming his own school called the Ulm School of Design in 1953, with artist Inge Aicher-Scholl and Otl Aicher in Ulm, Germany.

Originally basing their teachings of the Bauhaus school, Ulm School of Design developed a new education approach that integrated art and science. This unorthodox design education even included semiotics in its curriculum, which caused a bit of stir amongst the art and design snobs of the day. And maybe Bill and his friends were actually too ambitious with their education theories, because the school only lasted for 13 years before it closed.

After this foray, Bill started working heavily in architectural and industrial design. He also kept painting and doing graphic design, but his more commercial work in the 1950s might be what he is best known for today.

Max Bill's Ulmer Stool, (pictured above) was made in the 1950s, and is meant to be used either as an modular object that sits on the ground or as shelves mounted on the wall. So pretty! He also worked with Junghans, a Swiss timekeeping company, where he designed watches, clocks and scales, which are still available on the market. v v v (I die).

Being that Max Bill was so prolific much like his predecessors of the Bauhaus school, he worked and exhibited up until his death in 1988.

Towards the end of his life, architects and public planners in Germany and Switzerland began commissioning Bill to make large sculptures to be displayed in public spaces. Nearly all are still on view and are protected by a conservation trust started post-mortem by Max Bill's son.

I could go on forever about this guy but I need to go to bed. If you haven't familiarized yourself with his work, check it out. There's so much... the guy lived for 80 years and worked for almost 60 of them. Soooo coool.

Courtney Bagtazo, © Bagtazo 2016