Female Study: Marisol's Three Dimensional Portraits

The Party, 1965/6 at The Toledo Museum of Art

The first time I saw Marisol’s work was a vintage photo of The Party on Tumblr. I assumed Marisol was a man (despite the name), and also thought the image was a still from a film. I saved the photo and intended to find the film one day and even kept a copy of the photo on my cellphone (all 4 generations of them) to ensure I’d come back to it.

Fast forward many years later, I was at the Toledo Museum of Art during a visit with my in-laws, and I walk into a room where The Party is on view. I was speechless… The work was so beautiful, and so clearly made by a woman; and what the hell was I thinking not looking into it sooner!

The Whitney most recently exhibited Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019, which included Marisol’s Women and Dog (1964). Seeing her work again inspired me to finally sit down and do proper research on her.

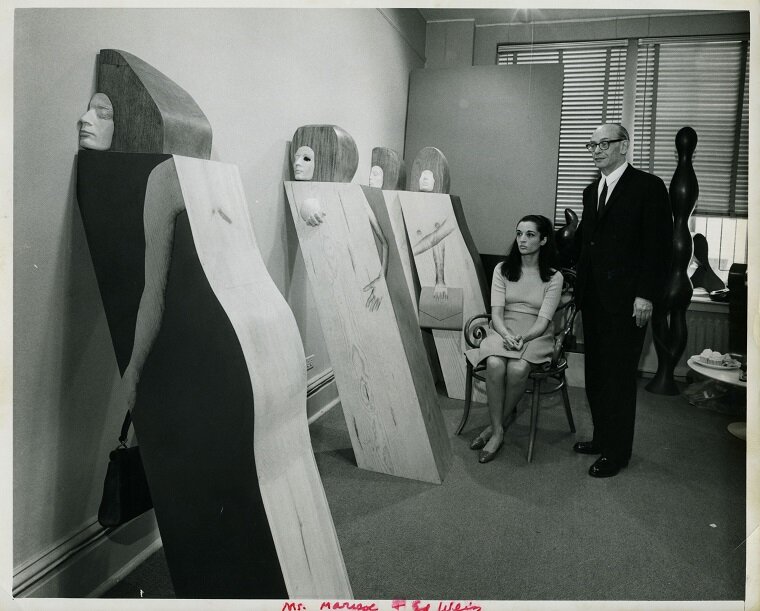

Women and Dog (below) is a work in self portraiture. The multi-faced sculptures are plaster molds of Marisol’s own. Because plaster molds always come out differently, the faces on the sculpture are all slightly different. The black and white photograph pasted onto the middle woman’s face is a photograph of Marisol, and the child is a portrayal of herself in her youth. The majority of the sculpture is made of wood that Marisol cut and glued together, except for the bow on the child’s hair, the purse, the leash, and the taxidermy dog’s head, which are all found objects.

Much of Marisol’s works are so deeply personal, I am enamored by them. I often try to talk myself out of designing something because of how personal it is, but I’ll start quieting that noise knowing that Marisol and other female artists in particular have successfully done very personal works that still appeal to others.

Women and Dog, 1964

Maria Sol Escobar was born in 1930 in Paris. Her parents were heirs of Venezuelan oil and real estate wealth, and bit nomadic, so they spent Marisol’s early years between Paris and Caracas. After her mother’s suicide, when Marisol was only 11 years old, she was sent to a boarding school on Long Island, New York. During this time, Marisol took very drastic measures to cope with her grief, including seldom speaking until her early 20s, and walking on her knees until they bled (which is a catholic practice of asceticism practiced widely historically, and still in practice, though uncommonly, today). Eventually in 1946, Marisol reunited with her father and her siblings, when the family settled in Los Angeles.

When Marisol relocated to Los Angeles, she studied art at Otis and Jepson (in Westlake, today’s MacArthur Park), before studying in Paris at École des Beaux-Arts in 1949. Not liking the strict structure at Beaux-Arts, Marisol finished her studies at the Art Students League at the New School for Social Research in New York City.

Though Marisol is mostly known for her boxy assemblage sculptures, The Guardian called her “the forgotten star of pop art” when she died in 2016. Andy Warhol also called her the “first girl artist with glamour,” but Marisol had been making her sculptures prior to the pop art movement, and it was her now lesser known expressionist paintings that initially held the art world’s attention in the 1950s.

In the early 1960s, Marisol began experimenting with what she called, “three dimensional portraits,” making wood sculptures such as The Party. Technically speaking, this work is considered assemblage art, given the fact that she took many different media and found objects to assemble her sculptures, but since the pop art movement was developing during that period, Marisol got lumped in as the ‘first lady of pop art’ for her use of mundane ordinary objects in her work.

Being considered the first female anything in the 1960s automatically makes one a bad ass, but right as she was beginning to create her three dimensional portraits, she attended an all male event in New York known as The Club, which really put her on the map. The Club was a gathering place of major (straight male) players of NYC’s art scene. Women, gay men, and communists were not permitted to attend the meetings (lol), but one night Marisol showed up wearing a white mask. (Some versions of the story say she was invited, others say she just showed up). A woman’s presence at The Club was enough to drive everyone mad, but the tension was only heightened by the fact that she wouldn’t take the mask off, even after being asked several times. Eventually when she finally obliged, her face was also painted white just like the mask. Fucking. Bad. Ass.

There’s not much record of what happened after she removed her mask, other than she didn’t say much, but it’s a legendary story that sets the tone for her attitude towards the status quo.

Marisol in the 1960s. Marisol dropped her surname ‘Escobar’ to renounce her affiliation with the patriarchy in the 1950s. She also thought it would help her become more memorable.

Though trained in the arts, Marisol was self taught in sculpting and woodwork, having been inspired by Pre-Colombian art on a trip to Mexico in 1950. This is when she moved from abstract expressionism to create her own style. Throughout the 50s she worked in metal and clay, but by the end of the decade, she had established her iconic totemic sculptures of wood. Her timing was such that it synced up with the pop art movement, which briefly led to her stardom.

With the help of her beauty and mystery (she was reportedly mostly silent at art appearances), Marisol became a fashion icon and New York it-girl as a result of a Glamour Magazine cover story, and her hanging with Andy Warhol. (Warhol had Marisol star in two films, The Kiss and 13 Most Beautiful Girls). In the Glamor spread, Marisol is shown wearing a bow in her hair, looking as elegant as Audrey Hepburn, posing on her table saw. I love seeing women subvert traditionally male dominated mediums. Looking cute next to a table saw? I die.

Marisol in 1968: ‘the first girl artist with glamour’ Photograph: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

But Marisol didn’t much care for the limelight and quietly drifted into near obscurity in pop culture by the 1970s, though she continued to work in her medium, and was well exhibited and collected until her death in 2016.

Much of Marisol’s work focused on her personal life, and her sculptures often centered on her family, or various versions of herself. Women and Dog (above) as well as Women Sitting on a Mirror (below) are abstractions of Marisol at different stages of her life, whereas The Family and Mi Mamá y Yo (both below) are scenes of her family prior to her mother’s suicide.

The Family, 1963

Mi Mamá y Yo, 1968

Women Sitting on a Mirror, 1965/66

Aside from her self portraits and personal motifs, Marisol also worked on sculptures of prominent political figures, including pieces of the Kennedy Family, the Royal Family (below), Lyndon B Johnson, and even George W Bush. When asked about her George W sculpture, Marisol mentioned in an interview that she was commissioned to make the sculpture, and was paid a lot of money to do so, but “they never used it… maybe they didn’t like it.” I’m just hoping she purposely portrayed him in an unflattering light as she had done with LBJ in the 60s.

In this vein, Marisol also made sought after sculptures of generals and other figures from pop culture and history, including Marcel Duchamp and John Wayne.

The British Royal Family, 1967

Marisol posing like a badass with her saw and “The Kennedys,” 1964

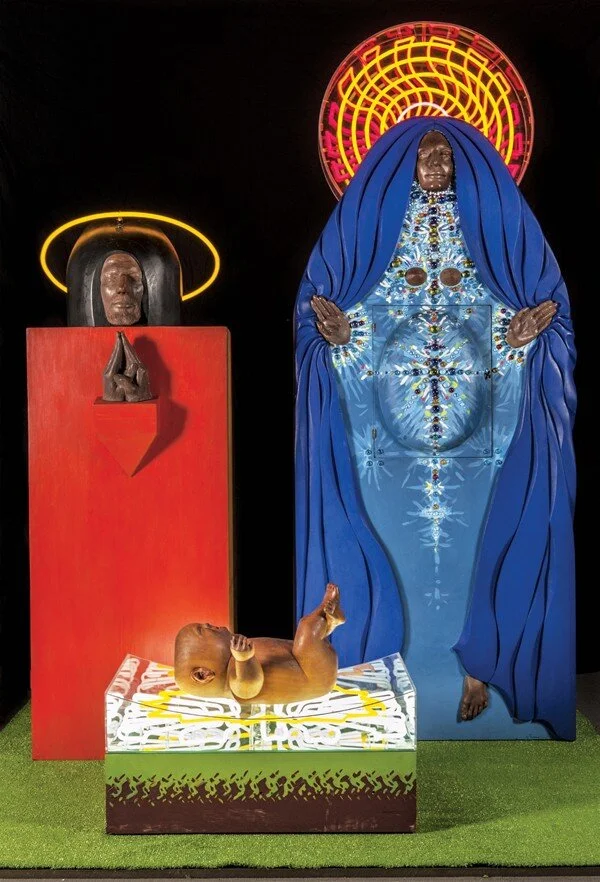

Marisol had always been religious, so some of her works recreated Catholic motifs as well, but even here she included the likeness of her own face.

Self Portrait with The Last Supper, 1982-84

The Holy Family, 1969

In this article I have chosen to focus on Marisol’s assemblage sculptures, because those are what caught my attention first, but she did also make amazing paintings and more “traditional” sculptures as well. Marisol was a woman of very few words, so in my research I found mostly people speaking for her, but I was able to find a quote in the Paris Review from an interview in the 1968 about how she began her totemic work. Simply put she said, “In the beginning I drew on a piece of wood because I was going to carve it. And then I noticed that I didn’t have to carve it, because it looked as if it was carved already.”

In my research, I found one audio interview through The Whitney (linked below), where Marisol’s soothing voice is describing Women and Dog. I hear that same voice explaining the above, and her simple answer makes perfect sense to me, because in her voice I can hear her feeling.

A more overt Pop Art piece. “Love,” 1964

Courtney Bagtazo, © 2020

Bibliography

Marisol (Marisol Escobar), MoMa

Watch and Listen: Marisol, Women and Dog, 1964, The Whitney

Marisol: The Forgotten Star of Pop Art , The Guardian.

The Curious Case of the First Lady of Pop Art, Spectator.

First Lady of Pop Art, Spectator

Marisol Escobar, Wide Walls.

Marisol, Albright Knox.

The Mask Behind The Face. David Colman, 2007. New York Times

Marisol, an Artist Known for Blithely Shattering Boundaries, Dies at 85. William Grimes, 2016. New York Times

Marisol. Dan Pipenbring, 2015. The Paris Review.

Tracking Marisol in the Fifties and Sixties, Marina Pacini. Archives of American Art Journal Vol. 46, No. 3/4 (2007), pp. 60-65