Female Study: Deborah Turbeville's Soft Frustration

Parco, 1964

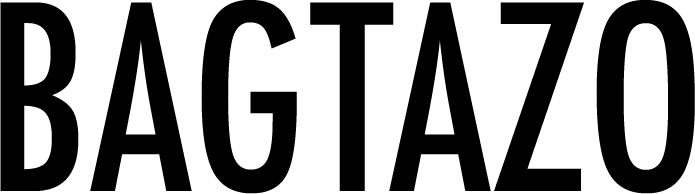

Being in quarantine on May Day (Beltane), made me think of Deborah Turbeville’s photographs. Her imagery often takes place indoors, or even when outside, the photographs express a somewhat isolated sentiment. But within the photographs, the soft underside of femininity shows through, similar to the way a reluctant spring pushes through after winter.

The models in Turbeville’s work are portrayed idle, lounging around, appearing to be in lamentation or sorrow. Here in NYC, being as stormy as it is on this day of spring rites, the mood Turbeville captures in her photos from the 1960s until her death in 2013 seemed fitting to explore.

Turbeville’s work is sometimes described as brooding, and she is credited for helping bring an edge to fashion photography previously absent in commercial work. (Alongside Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin). But while I absolutely adore Newton and Bourdin’s work, the male gaze is clear, whereas Turbeville’s work is soft and far less sexualized. Her photographs almost look like classical paintings, but with a very strong fashion perspective and an eerie air about them.

Starting in the 1970s, fashion used the “sex sells” notion widely in its imagery, a theme that is alive and well today, but Turbeville refused these conventions, avoiding the stereotypical depictions of glamour. Often feeling shy or turned away from society herself, Deborah Turbeville sought to reflect these emotions in her work. In Women on Women, a book about female photographers, photographing female models, Turbeville states, "there is the gnawing feeling that something is wrong. My work is not complete if it does not contain some vestige of this frustration in the final prints.” In 2015, Vogue said that, “Turbeville’s work grappled with the interior life of women and their changing place at a time when longstanding gender roles were as distorted as the reflections from a disco ball.” And while traditional notions of femininity are in question today even more than they were in the 1970s, what I love about Turbeville’s aim to portray frustration, is that she does it with a softness that accurately expresses the frustrating pressure to: “Be pretty, be gentle, and by all means, take the bullshit and don’t speak out.”

Though no one has ever actually said those words to me, personally, I feel that being raised gendered female, this was implied, and me and my fellow sisters tacitly agreed to accept what was expected of us, even now when the expected gender roles are much less clear. But of course, many women have been frustrated with this reality throughout history, though I think few have been able to express it so well without words as Deborah Turbeville has.

Deborah Turbeville was born to an “eccentric household” in a Stoneham, a suburb just outside of Boston, Massachusetts in 1932. The isolation that shows in her work mirrors the isolation she said was felt growing up. Her family was wealthy and thought that isolation would maintain their distinguished reputation; Living in an almost communal-like setting in a large house with many extended family members constantly present. Turbeville describes this “little world” of her parents, aunts, and grandmother as a place where they protected her, allowing her to do as she wanted, seldom coming in contact with children, living in a world of adults.

Growing up, I always associated having non-family member friends as something Americans did, because in my Filipino family, we almost exclusively socialized with family members, so the “little world” Turbeville describes very much resonates with me. But where her world was classical in aesthetic, mine was mid-century and very dull. But I do believe that feeling isolated from the rest of society is partly what caused my angst and sparked the need to create a world within the little world I lived in, in attempt to escape the mundane. Turbeville did the same her whole life, making things against the grain from an early age, working almost entirely self-taught.

After schooling, Deborah Turbeville moved to New York where she worked as an in-house fit model and assistant for the fashion designer Claire McCardell. Eventually, Turbeville became editor at Harper’s Bazaar in 1970 (a history I cannot find much information about online), but she grew bored of the work, and began focusing on her photography that she had started in the 1960s.

Through her network in New York’s fashion industry, Turbeville was soon published in major fashion magazines for editorials, and campaigns for everyone from Comme des Garcons to Bloomingdales.

From Vogue in 2017:

When these images were first published, they represented a radical break in the world of fashion photography, which at the time was pretty much stuck in two trenches: an obsession with sexiness verging on the semi-pornographic, and a sunny inane cheerfulness. Turbeville chose a third path—a haunting hyper-realism, a notion of fashion photography that relied on the mere suggestion of clothing.

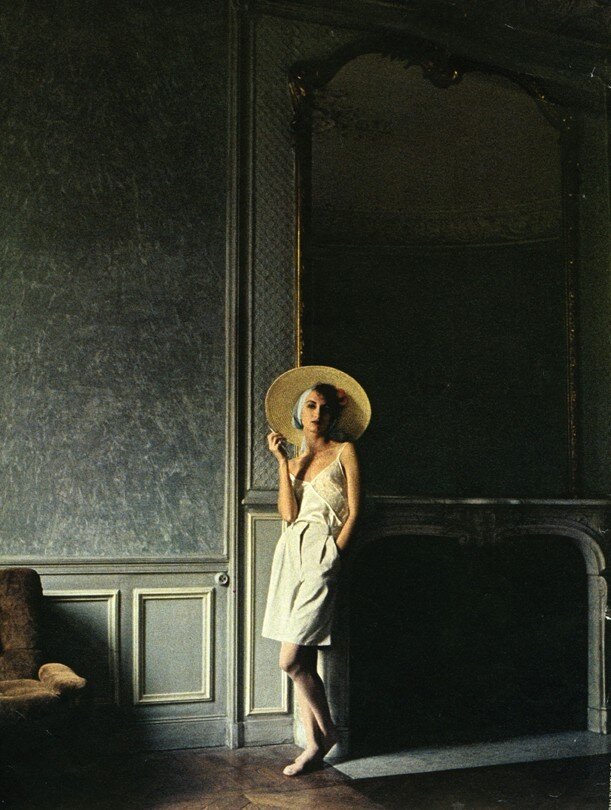

What interests me the most about her work is that going against the grain for her meant maintaining a sort of classical element. This seems counter-intuitive but in practice the result is remarkable. Classical sculptures and paintings have portrayed women gazing away from the audience, but the quiet sorrow expressed in Turbeville’s work is distinct to her alone. Partly because of the signature pastel, sepia and black and white pallet always shown through a grainy print, but more so as a result of the negative space, and eerie feeling present in her photographs, Turbeville subverts the classical world. Using ballet motifs, changing rooms, bath houses, decaying woods and poorly maintained classically decorated interiors, Deborah Turbeville convey a message not just of beauty or tragedy common to classical artworks, but invokes the question, “what’s the matter?” Or as the times put it in her obituary, she conveys “an elegiac landscape defined more by absence than by presence.”

By physically manipulating her negatives and intentionally overexposing her photographs, (also want to mention she had an assistant and collaborator named Sharon Schuster who helped her with this technique, sometimes taping or scraping the film before printing), Turbeville added a further element of distress to her already haunting images captured in the frame.

And while it may be commonplace today for fashion photographs to take place is derelict or decrepit locations, or to shoot with expired film, this was not the case in the 1970s when Deborah Turbeville hit the scene. Her now famous bathhouse photographs were shocking, as the condemned locale seemed disgusting to the masses. But what allures the viewer despite this shock, is that Turbeville was able to access the private lives of women, something that wasn’t shared publicly at the time. Now often fetishized, without Turbeville, the public had not had access to view this exclusive world, especially from perspective of a female.

I think my favorite things about Deborah Turbeville is that she subverted the classical image, forged an entirely new aesthetic, and that she is mostly self-taught. She did however, attend a course taught by the venerable Richard Avedon, and learning this bit of information, I now see his teaching influence in her work, but the distinctive element of isolation in her images are what makes them so special.

In the past I shied away from doing Periodicals on more commercial, or what I think are well-known artists, but after quarantine I no longer feel the need to put any further rules or constraints on sharing my research. I hope that even if you are familiar with her work, this has been informative and enjoyable for you.

TY for tuning in.

Images from Jacquelinne Kennedy Onasis (then editor of Doubleday Magazine) commissioned work, “Unseen Versailles, 1980-81. Last image is a self portrait!!

Bibliography

Celebrating the Haunted Beauty of Deborah Turbeville and Comme des Garçons. Vogue, 2017

Deborah Turbeville's magical photographs of Versailles in a new exhibition. Architectural Digest, 2014

Why the Women of Deborah Turbeville Are Timeless: From Her Bathhouse Beauties to Her Memorable Nudes. Vogue, 2015

Deborah Turbeville, Photographer Dies at 81. New York Times, 2013

Courtney Bagtazo, © Bagtazo, 2020